It’s hard to communicate to non-gamers, and even to those of us who haven’t lived within the realm of Massively Multiplayer Role-Playing Games just how much a world-within-a-world they are. A microcosm not only in the size of the digital landscape that you inhabit, but more poignantly, the relationships and the culture that like a prism, reflect and interpret the ones we hold with each other in the real world. As art imitates life, and gives us a lens to see aspects of life more clearly than we can with mere day-to-day observation, MMOs cast a long shadow that can render parts of human existence with surprising clarity.

Because there are so many people who play MMORPGs, they have been ripe for representation in popular media. Webcomics in particular, being a medium that has come of age alongside online games, have had numerous stories that spell out these epic tales. Most of them are autobiographical in some sense, or comedic, using the world in miniature to have motley crews play out daring adventures, with perhaps a prat fall or two. Some use the digital realm as inspiration for their own stories, using a game they’ve played as a launching point for creating a whole new world of fantasy. Most are heroic. Heroism is, after all, what MMOs are all about. It’s a rare thing in stories to talk about failure, about impending defeat, the post-apocalyptic genre being an exception.

Page 21 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

Enter the world of Faction, a webcomic begun in 2016. The story takes place in a cyberpunk setting, where people play a massively online multiplayer game called MUlate. Not unbelievably, this game has a world-wide following of fans and spectators, where sponsored players make boku bucks by being the best, the flashiest, the most destructive. Emma Martina, known by her callsign Crashback, is Red faction’s champion, a “tank” class who wields oversized powered gauntlets to crush and maim her enemies, and seize victory on behalf of her team. Well, using the present tense might be a bit inaccurate. A series of setbacks, poor leadership from the top (a problem many MMO players will sympathize with), and dwindling alliances have put Red on the back foot. In fact, they are on the verge of being eliminated from the game, and once you lose in MUlate, you can never come back.

This story may seem strange and detached from our world to those unfamiliar with the narrative nature of video games. The language is bizarre, and at best the game itself seems like an isolated simulacrum, perhaps fascinating in some way, but ineffable nonetheless. However, to MMO veterans, who understand on a base level that the world we create within the game is essentially a parallel social order, a world-in-miniature where we remake the organizations, the contracts, and the web of relationships which however crude and simplistic mimic the birth of tribes and familial clans of old, Faction is deeply compelling. The guild leader who is full of himself, detached from the realities on the ground, a buffoonish entity whose ego leads him to conflate his identity with that of the guild itself? Check. The veteran player who is the real reason the guild manages to survive at all, but due to machinations, or just apathy, barely concerns themselves with the functioning of said guild? Check. The eager newbie, who has great ideas but is stuck in the twisted web of guild hierarchy, unable to actualize the strategies and restructuring that might save the guild from extinction? Check, check, and check.

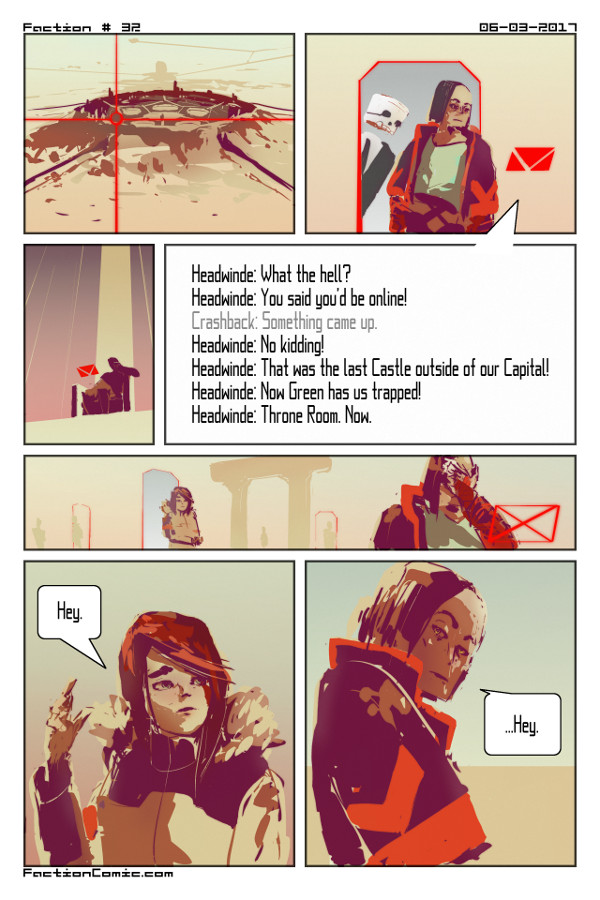

Page 32 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

The reason why these archetypes resonate is not just because, as MMO players, we have actually encountered these people before, sometimes over and over again. (It is important to note that for many of us, far greater shades of complexity color the people we have called guildmates, enemies and friends.) Stripped of their outer wrapping, these people exist in the real world as well; as our bosses and fellow employees, and in our politicians, albeit on a far greater scale, one that can be difficult to imagine, to accurately place these caricatures within a setting so grand and serious. Yet when we talk about an obsequious manager who sets unreasonable goals in order to get good performance reviews, sucking up to their superiors and presenting themselves as the pinnacle of competence while it is only due to the herculean effort being put out by their team that anything is getting done at all, we are seeing the guild officer who acts in exactly the same way with their guild leader. The parallels are not a coincidence, and any person who has been seduced by the rich ecosystem of connections and interactions inherent in any MMORPG recognizes this.

Seeing it played out in a story, rather than in-game, is tantalizing, all the more so when the writers of Faction refuse to pull any punches. While the “drama,” as we RPGers call it, can seem infantile to outside observers, the feelings and the emotions we experience in-game are very real, because it’s not about the game. We’re not playing when a guild devolves into internecine warfare, or players have a falling out; that’s actual people having problems with other people, and we get hurt regardless of the screens and pixels that lay between us. That is often what draws us gamers into MMOs. The relationships we have are genuine, even if the stage which we perform them on is little more than a digital dream. Faction puts that front and center by making the crisis facing Red Team an existential one. Guilds ebb and flow in MMOs, and it is entirely believable that Red was once a powerhouse that put all the other factions to shame. But mismanagement is the bane of all empires (an echo uncomfortably familiar in our own United States). The degradation found within the power dynamic stems from personal issues, another scenario all too familiar with gamers.

The rot set in when Emma appointed a friend, Seong (known by his callsign Headwinde), as Faction leader; over time they grew distant, leading Emma to become cynical and apathetic, while the crushing weight of maneuvering Red Team’s future alone led to Headwinde’s ego inflating to compensate. Both are sympathetic figures when their guard is down; are we experiencing deja vu again, boys and girls? Because although personal conflict leads to attempts to paint former friends as stupid or malicious, in truth most of the wiser gamers know fault tends to lie with both sides. It is this subtle application of the brush of character writing that makes the story alluring.

Headwinde is the ruler of a doomed kingdom, and while he knows that some of the missteps are his fault, he nevertheless is devoted to the survival of his faction. He is cognizant that there are hundreds to thousands of people who will be locked out of the game forever if Red loses their last bastion. While earlier in the comic he is portrayed as an egomaniac, a hothead and arrogant, as the burden he has been forced to bear becomes more apparent we begin to understand how he got to be this distorted caricature, as well as glimpsing the strong and intelligent bulwark he might have been in the beginning.

Page 75 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

Crashback, for all the fact that she is a revered celebrity, is revealed to be unhappy, in financial trouble, and a loner. A relative giant of a person in the real world, her considerable height seems to be a metaphor for her isolation. She towers above other people, and in doing so appears removed from the ties of social interaction and friendship. Because she earns her living as a sponsored player, she relies on nameless brands and companies to give her a paycheck. With Red’s troubles and potentially imminent demise, the flow of cash has dried up, and she’s left relying on total strangers to pay her public transit tickets. Her part-coach, part-manager, who goes by the tag Advocracy, is present only in text message conversations, trying to mollify her with promises of negotiations with sponsors, and cryptically referencing the possibility of her being able to return to the game as a member of another faction should Red lose. It’s sad that Advocracy seems to be the only person in Emma’s corner, and even that is ethereal, a non-present presence that the reader is left unsure of whether he personally cares of Emma, or merely as a professional relationship.

Page 41 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

This humanizing of those who are initially presented as one-dimensional is Faction’s greatest strength as an enjoyable piece of fiction. Reading about heroes and villains who have their set roles is entertaining yet ultimately unfulfilling, because real life is more complicated than that. As Faction delves into its characters, adding layers that are wonderfully unwound through encounters and changes in scene, you get a sense of these being real people, with flaws, failures, and triumphs. To us gamers, it simply reiterates, in a gorgeously illustrated setting, what we already knew; that the real world and the digital world are mirrors, in which we catch glimpses of our true selves, in the midst of all that playing and posturing. And occasionally, we learn something new about who we are, and who we can become.

Part of the allure of Faction comes from its grand and atmospheric illustrations. The graphic artist Heliotrope works the magic of transposing narrative to action-packed page. Go on, give yourself the treat of examining it indepth. He employs a wonderful, elegant method of abstracting characters who are farther in the background, rendering them in deft digital brushstrokes that harken to traditional East Asian painting. With his rich foregrounds, he packs in as much emotion as he can scrunch into a face.

The austere beauty of the environments is briefly sketched, like a landscape painting. It was chosen early on that there would be an elemental connection between a team’s home environment and their color; Red, not surprisingly, being aligned with Fire. Scorched forests, smoldering pools of lava, and sharp, monumental boulders comprise their territory.

Page 62 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

Page 48 of Faction. Illustrated by Heliotrope.

His style offers a syncretic blend with the writing, where our brief exposure to the characters comes across in big, bold strokes. We never get enough time to obtain a complete picture of each person, but the impressions we receive tag them with strong personalities. When Opticular, the jaded but tactically competent Medium class, gets first introduced, a forlorn guardian welcoming his woefully inadequate reinforcements, the complex tapestry which is he gets deconstructed and laid out in just a handful of pages.

The Mediums are not fighters; they are a support class, which in RPG parlance means they aid their allies, rather than being frontline fighters. They also appear to be a pet class, which will engender invariable groans from the MMO veterans among us. The lameducks of MUlate, they’ve been cast aside into this one castle by Headwinde. Left to rot, Opticular whiles his time away lamenting Red’s hubris and blindness.

His restrained and constricted competence is bursting at the seams with irritation, at forced impotence by Red’s leader. Headwinde apparently has a problem with Mediums, thinking them an inferior class. Having left them to rot, these orphans were gathered together by Opticular, serving a lone vigil with insufficient manpower and no reinforcements.

Opticular might be the jaded cynic, but only as a part of a larger enterprise of dysfunctionality. As a paraphrasing of a Chinese saying might go, when the emperor is misguided, all under heaven and earth falter. Headwinde and Crashback’s alienation has led to a fractured leadership for Red, where sycophants and the inexperienced create holes in successful organizing like a good swiss cheese. Or a rat’s nest. For those who have had the misfortune of personally experiencing dysfunctional guilds, the view might well have looked like the latter rather than the former.

Hope is its own emotional thread throughout the story. Warsparks, the intrepid newbie who is all hyped up to kick some ass for her team, plays a counterpart to Emma’s resignation, Seong’s arrogance and Opticular’s apathy. It is due to her quick thinking, and accurate assessment of Red’s assets, that allowed her, Crashback and Opticular to succeed in a fierce engagement. She’s smart, she isn’t tied down with baggage, and she wants to win. Her burning brightly offers the potential for a way out. While for everyone else, Red’s eventual demise seems inevitable, excluding Headwinde’s bull-headed assertion of resilience, with her each step seems to light the way towards a possible future.

It’s striking because as MMO players we’ve experienced this, hopefully to a good conclusion. Good people, and good players, often find ways to bring the guild back on track. It takes positive thinking, some creativity, and willpower, but it can happen. While the future of Red Faction is uncertain, one can enjoy their journey, and find some moments for self-reflection in the process.

The team that brings you Faction are Alex Palm and Alexander Wozny, Heliotrope, and ClockworkJordan.

You can read Faction here. Start at the beginning.

When I contacted the Faction Team, Heliotrope very kindly accepted my offer for an interview. I’ll be posting the results of that conversation in two weeks, so stay tuned.